My View From Las Vegas

Tuesday, March 29, 2005

STYLE Our Town By MAURA EGAN

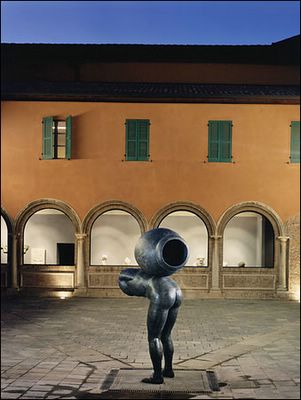

Reggio Emilia is a picturesque city about an hour east of Milan. Old men ride bicycles over the cobblestone streets, the women shop the open food markets in the piazza (the region could be called ''the cholesterol belt of Italy,'' since the country's top-shelf Parmigiano Reggiano, Parma ham and pasta are produced there) and the swarming schoolchildren look like something out of a Fellini film. It's all very quaint and Old World until you step into the cloisters of the nearby Church of San Domenico and discover a bronze figure -- headless, armless, genderless, a large urn sprouting from its back -- smack in the center of the courtyard. Industrial-type music, the sounds of a busy city, played every evening at dusk, accompanies the piece. This gleaming abstract sculpture, ''Less Than,'' by the Minimalist artist Robert Morris, is part of a continuing project by the Italian fashion house MaxMara and Reggio Emilia to introduce contemporary art into the daily life of the city. Last summer, Sol LeWitt painted the kaleidoscopic ''Whirls and Twirls 1'' on the ceiling of the reading room of the Panizzi Library, a 18th-century building in the center of town. ''We started with the easiest, the pretty colors,'' says MaxMara's chairman, Luigi Maramotti, who recognized that more challenging work might stump the natives. The Maramotti family has always had a big investment in the town, ever since Luigi's father, Achille, founded the company there in 1951 with the goal of bringing Paris high fashion, at affordable prices, to the ladies of Italy. The family is the major shareholder in the local bank, Credito Emiliano (which warehouses 300,000 wheels of the locally produced Parmesan, a vestige of a time when farmers left their cheese in the bank vaults as a guarantee for their loans); it owns the luxury hotel Albergo delle Notarie and a restaurant, not to mention acres of farmland on the outskirts of the city. Forty-five years later, Luigi Maramotti presides over the $1.5 billion business, which boasts 23 different clothing lines and more than 1,800 stores around the world. (Achille died in January at age 78.) And if Prada is known for its intellectual rigor and Dolce & Gabbana for va-va-voom sexiness, MaxMara has positioned itself as the ''quiet giant'' of the fashion industry. The company has maintained a value-over-frills philosophy, designing classic pieces like the perfect camel coat that outlast the whims of fashion. As Domenico Dolce, who scissored-out patterns there years ago (as did Karl Lagerfeld, but MaxMara doesn't believe in flaunting its designers like box-office stars) explains, ''On their level, nobody does it better.'' You witness that level of perfection in Maramotti, perched this day on an ergonomic chair behind an expansive glass desk in his office. In 2003, MaxMara moved into new headquarters, a modular affair designed by the London-based firm John McAslan & Partners. Maramotti's passion for details is wide-ranging -- from the ply of cashmere used for a camel coat (''The fabric is always the starting point,'' he says) to the choice of art that hangs in his office (a triptych by his friend Peter Halley, the American painter) to the location of the company cafeteria. He read reports that doctors advise humans to walk half an hour each day, so he made sure the canteen and the parking lot were situated a healthy distance from the actual offices. Company policy forbids eating at your desk, and employees are thus forced to get some fresh air during the workday. There are even buckets of umbrellas stationed at the exits for rainy days. Luigi, along with his brother, Ignazio, who is managing director, and sister, Maria Ludovica, who is in charge of product development, wanted to implement these utopian ideals outside of the workplace, which led to their current roles as modern-day Medicis. In addition to the artists' project, the family will open its museum-worthy art collection to the public in 2007. Achille amassed one of the most important collections in the country, with works by de Chirico, Morandi and Richter. ''Achille was one of these mythic figures,'' Peter Halley says. ''He was part of this generation of entrepreneurs after the war who believed that business and culture went hand in hand. Success meant participating in the arts.'' A large-scale piece by Richard Serra will be completed and installed in an industrial complex north of the town in 2006. The latest and possibly most ambitious component in the city's cultural overhaul is the design of the new train station, which will be on the high-speed line that links Milan to Rome. Maramotti, naturally, wanted a boldfaced architect for the project. He championed Santiago Calatrava, who put his native Valencia on the design map with his City of Science Museum and Planetarium and is heading up the $2 billion transit hub for the World Trade Center. ''I just called him up and asked him,'' he says matter-of-factly. But because it was suspected that townsfolk might resist a metal-and-glass structure jutting out of their serene countryside, Calatrava was invited to present his ideas at a town meeting. ''He was a hit,'' Maramotti says triumphantly. ''He drew pictures and then gave them all away to the children.'' Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company