My View From Las Vegas

Thursday, March 31, 2005

Medical Costs and Doctors Salaries

PIECEWORK

by ATUL GAWANDE

Medicine’s money problem.

Issue of 2005-04-04

Posted 2005-03-28

To become a doctor, you spend so much time in the tunnels of preparation—head down, trying not to screw up, trying to make it from one day to the next—that it is a shock to find yourself at the other end, with someone shaking your hand and asking how much money you want to make. But the day comes. Two years ago, I was finishing my eighth and final year as a resident in surgery. I had got a second interview for a surgical staff position at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, where I had trained. It was a great job—I’d get to specialize in surgery for certain tumors that interested me, but I’d also be able to do some general surgery. On the appointed day, I put on my fancy suit and took a seat in the wood-panelled office of the chairman of surgery. He sat down opposite me and then he told me the job was mine. “Do you want it?” Yes, I said, a little startled. The job, he explained, came with a guaranteed salary for three years. After that, I would be on my own: I’d make what I brought in from my patients and would pay my own expenses. So, he went on, how much should we pay you?

After all those years of being told how much I would either pay (about forty thousand dollars a year for medical school) or get paid (about forty thousand dollars a year in residency), I was stumped. “How much do the surgeons usually make?” I asked.

He shook his head. “Look,” he said, “you tell me what you think is an appropriate income to start with until you’re on your own, and if it’s reasonable that’s what we’ll pay you.” He gave me a few days to think about it.

Most people gauge what they should be paid by what others are paid for doing the same work, so I tried asking various members of the surgical staff. These turned out to be awkward conversations. I’d pose my little question, and they’d start mumbling as if their mouths were full of crackers. I tried all kinds of formulations. Maybe they could tell me how much take-home pay would be if one did, say, eight major operations a week? Or how much they thought I should ask for? Nobody would give me a number.

Most people are squeamish about saying how much they earn, but in medicine the situation seems especially fraught. Doctors aren’t supposed to be in it for the money, and the more concerned a doctor seems to be about making money the more suspicious people become about the care being provided. (That’s why the good doctors on TV hospital dramas drive old cars and live in ramshackle apartments, while the bad doctors wear bespoke suits.) During our hundred-hour-week, just-over-minimum-wage residencies, we all take a self-righteous pleasure in hinting to people about how hard we work and how little we earn. Settled into practice a few years later, doctors clam up. Since the early nineteen-eighties, public surveys have indicated that two-thirds of Americans believe that doctors are “too interested in making money.” Yet the health-care system, as I soon discovered, requires doctors to give inordinate attention to matters of payment and expenses.

To get a sense of the numbers involved, I asked our physician group’s billing office for a copy of its “master fee schedule,” which lists what various insurers pay staff doctors for the care they provide. It has twenty-four columns across the top, one for each of the major insurance plans, and, running down the side, a row for every service a doctor can bill for. Our current version goes on for more than six hundred pages. Everything’s in there, with a dollar amount attached. For those who have Medicare—its payments are near the middle of the range—an office visit for a new patient with a “low complexity” problem (service No. 99203) pays $77.29. A visit for a “high complexity” problem (service No. 99205) pays $151.92. Setting a dislocated shoulder (service No. 23650) pays $275.70. Removing a bunion: $492.35. Removing an appendix: $621.31. Removing a lung: $1,662.34. The best-paid service on the list? Surgical reconstruction for a baby born without a diaphragm: $5,366.98. The lowest-paying? Trimming a patient’s nails (“any number”): $10.15. The hospital collects separately for any costs it incurs.

The notion of a schedule like this, with services and fees laid out à la carte like a menu from Chili’s, may seem odd. In fact, it’s rooted in ancient history. Doctors have been paid on a piecework basis since at least the Code of Hammurabi; in Babylon during the eighteenth century B.C., a surgeon got ten shekels for any lifesaving operation he performed (only two shekels if the patient was a slave). The standardized fee schedule, though, is a thoroughly modern development. In the late nineteen-eighties, insurers, both public and private, began to agitate for a more “rational” schedule of physician payments. For decades, they had been paying physicians according to what were called “usual, customary, and reasonable fees.” This was more or less whatever doctors decided to charge. Not surprisingly, some of the charges began to rise considerably. There were some egregious distortions. For instance, cataract-surgery fees (which could reach six thousand dollars in 1985) had been set when the operation typically took two to three hours. When new technologies allowed ophthalmologists to do these operations in thirty minutes, the fees didn’t change. Billings for this one operation grew to consume four per cent of Medicare’s budget. In general, payments for doing procedures had far outstripped payments for diagnoses. In the mid-eighties, doctors who spent an hour making a complex and lifesaving diagnosis were paid forty dollars; for spending an hour doing a colonoscopy and excising a polyp, they received more than six hundred dollars.

This was, the federal government decided, unacceptable. The system discouraged good primary care, and distorted specialty care. So the government determined that payments ought to be commensurate with the amount of work involved. The principle was simple and sensible; putting it into practice was another matter. In 1985, William Hsiao, a Harvard economist, was commissioned to measure the exact work involved in each of the tasks doctors perform. It must have seemed a quixotic assignment, something like being asked to measure the exact amount of anger in the world. But Hsiao came up with a formula. Work, he decided, was a function of time spent, mental effort and judgment, technical skill and physical effort, and stress. He put together a large team that interviewed and surveyed thousands of physicians from almost two dozen specialties. They analyzed what was involved in everything from forty-five minutes of psychotherapy for a patient with panic attacks to a hysterectomy for a woman with cervical cancer.

They determined that the hysterectomy takes about twice as much time as the session of psychotherapy, 3.8 times as much mental effort, 4.47 times as much technical skill and physical effort, and 4.24 times as much risk. The total calculation: 4.99 times as much work. Estimates and extrapolations were made in this way for thousands of services. (Cataract surgery was estimated to involve slightly less work than a hysterectomy.) Overhead and training costs were factored in. Eventually, Hsiao and his team arrived at a relative value for every single thing doctors do. Some specialists were outraged by particular estimates. But Congress set a multiplier to convert the relative values into dollars, the new fee schedule was signed into law, and in 1992 Medicare started paying doctors accordingly. Private insurers followed shortly thereafter (although they applied somewhat different multipliers, depending on the deals they struck with local physicians).

There is a certain arbitrariness to the result. Who can really say whether a hysterectomy is more labor-intensive than cataract surgery? A subsequent commission has reëxamined and recalibrated the relative values for more than six thousand different services. Such toil will no doubt continue in perpetuity. But the system has been accepted—more or less.

Even with the fee schedule in front of me, I had a hard time figuring out how much I’d earn. My practice would primarily involve office visits, some general surgery (appendectomies, gallbladder removals, bowel and breast surgery), and—given my interest in endocrine tumors—a lot of thyroid and adrenal surgery. Each of these procedures pays between six hundred and eleven hundred dollars, and I could expect to do eight or so a week. Multiplying the numbers by forty-eight workweeks in a year, it seemed that I could make a flabbergasting half-million dollars a year. But then I’d have to spend thirty-one thousand dollars a year on malpractice insurance, and eighty thousand dollars a year to rent office and clinic space. I’d have to buy computers and other office equipment, and hire a secretary and a medical assistant or a nurse. The department of surgery deducts 19.5 per cent for its overhead. Then, there’s the five to ten per cent of patients who get free care because they don’t have insurance. And, even when patients are insured, some pay far less than others. Studies also indicate that insurers find a reason to reject up to thirty per cent of the bills they receive.

Roberta Parillo is a financial-disaster specialist for doctors who is called by physician groups or hospitals when they suddenly find that they can’t make ends meet. (“I fix messes” was the way she put it to me.) At the time I spoke to her, she was in Pennsylvania, trying to figure out where things had gone wrong for a struggling hospital. In previous months, she’d been in Mississippi, to help a group of a hundred and twenty-five physicians who found they were in debt; Washington, D.C., where a physician group was worried about its survival; and New England, for a big anesthesiology department that had lost fifty million dollars. She’d turned away a dozen other clients. It’s quite possible, she told me, for a group of doctors to make nothing at all.

Doctors quickly learn that how much they make has little to do with how good they are. It largely depends on how they handle the business side of their practice. “A patient calls to schedule an appointment, and right there things can fall apart,” she said. If patients don’t have insurance, you have to see if they qualify for a state assistance program like Medicaid. If they do have insurance, you have to find out whether the insurer lists you as a valid physician. You have to make sure the insurer covers the service the patient is seeing you for and find out the stipulations that are made on that service. You have to make sure the patient has the appropriate referral number from his primary-care physician. You also have to find out if the patient has any outstanding deductibles or a co-payment to make, because patients are supposed to bring the money when they see you. “Patients find this extremely upsetting,” Parillo said. “ ‘I have insurance! Why do I have to pay for anything! I didn’t bring any money!’ Suddenly, you have to be a financial counsellor. At the same time, you feel terrible telling them not to come in unless they bring cash, check, or credit card. So you see them anyway, and now you’re going to lose twenty per cent, which is more than your margin, right off the bat.”

Even if all this gets sorted out, there’s a further gantlet of mind-numbing insurance requirements. If you’re a surgeon, you may need to obtain a separate referral number for the office visit and for any operation you perform. You may need a pre-approval number, too. Afterward, you have to record the referral numbers, the pre-approval number, the insurance-plan number, the diagnosis codes, the procedure codes, the visit codes, your tax I.D. number, and any other information the insurer requires, on the proper billing forms. “If you get anything wrong, no money—rejected,” Parillo said. Insurers also have software programs that are designed to reject certain combinations of diagnosis, procedure, and visit codes. Any rejection, and the bill comes back to the patient. Calls to the insurer produce automated menus and interminable holds.

Parillo’s recommendations are pretty straightforward. Physicians must computerize their billing systems, she said. They must carefully review the bills they send out and the payments that insurers send back. They must hire office personnel just to deal with the insurance companies. A well-run office can get the insurer’s rejection rate down from thirty per cent to, say, fifteen per cent. That’s how a doctor makes money, she told me. It’s a war with insurance, every step of the way.

When I was going through medical training, a discouraging refrain from older physicians was that they would never have gone into medicine had they known what they know now. A great many of them simply seemed unable to sort through the insurance morass. This was perhaps why a 2004 survey of Massachusetts physicians found that fifty-eight per cent were dissatisfied with the trade-off between their income and the number of hours they were working; fifty-six per cent thought their income was not competitive with what others earn in comparable professions; and forty per cent expected to see their income fall over the next five years.

William Weeks, a Dartmouth professor, has done a number of studies on the work life of physicians. He and his colleagues found that working hours for physicians are indeed longer than for other professions. (In 1998, the typical general surgeon worked sixty-three hours per week.) He also found that, if you view the expense of going to college and professional school as an investment, the payoff is somewhat poorer in medicine than in other professions. Tracking the fortunes of graduates of medical schools, law schools, and business schools with comparable entering grade-point averages, he found that the annual rate of return by the time they reach middle age is sixteen per cent per year in primary-care medicine, eigh-teen per cent in surgery, twenty-three per cent in law, and twenty-six per cent in business. Not bad, in any of these fields, but the differences are there. A physician’s income also tends to peak when he has been in practice between five and ten years, and then decrease in subsequent years as his willingness and ability to work the long hours wane.

All that said, it seems churlish to complain. Here are the facts. In 2003, the median income for primary-care physicians was $156,902. For general surgeons, like me, it was $264,375. In certain specialties, the income can be a good deal higher. Busy orthopedic surgeons, cardiologists, pain specialists, oncologists, neurosurgeons, hand surgeons, and radiologists frequently earn more than half a million dollars a year. Maybe lawyers and businessmen can do better. But then most biochemists, architects, math professors earn less. In the end, are we working for the profits or for the patients? We can count ourselves lucky that we haven’t had to choose.

There are, however, those who do choose—and manage to earn considerably more than most. I talked to one such surgeon. He had practiced general surgery at the same East Coast hospital for three decades. He loved his work, he said. He did not have an unduly heavy schedule. His office hours were from nine-thirty to three-thirty on just one day a week. He did about six operations a week. He had been able to develop a special interest and skill in laparoscopy—performing operations through tiny incisions using fine instruments and a fibre-optic video camera. And he no longer had to cover midnight emergencies. I asked him in some roundabout way how much he earned doing this. “Net income?” he said. “About one point two million last year.”

I had to catch my breath for a moment. He’d made more than a million dollars every year for at least the past decade. I wondered how it was possible, or even acceptable, to earn so much for doing general surgery. He was perfectly aware of the reaction. (As was his hospital, which did not want his or its name to appear in print for this article.) “I think doctors shortchange themselves,” he said. “Doctors are working for fees that are similar to or below plumbers or electricians”—professions that, he noted, don’t require a decade of school and training. He doesn’t see why doctors should let insurance companies dictate their compensation. So he accepts no insurance. If you decide to see him, you pay cash. If you then want to fight with your insurer for reimbursement, that’s up to you.

The fees he charges are what he finds the market will bear. For a laparoscopic cholecystectomy—removal of the gallbladder, one of the most common operations in general surgery—insurers will pay surgeons about seven hundred dollars. He asks for eighty-five hundred dollars. For a gastric fundoplication, an operation to stop severe reflux of stomach acid, insurers pay eleven hundred dollars. He charges twelve thousand dollars. He has had no shortage of patients.

It’s not clear how easily others would replicate his success. After all, he works in a large metropolis, where many people have either incomes or insurance policies generous enough to accommodate his fees. He’s also something of a star in his field. “I know in my heart that I can do things that other surgeons can’t,” he told me.

But suppose I did what he did—refused to deal with insurance and charged what the market would bear. I would not make millions, but I could make a lot more than I otherwise would. I’d avoid all the insurance hassles, too. Still, would I want to be a doctor only to those who could afford me?

Why not? the surgeon was asking. “For doctors to think we have to be altruistic is sticking our heads in the sand,” he told me. Everyone is squeezing us in order to make money, he said—everyone from the supply companies that we pay to the insurers who are supposed to pay us. “The C.E.O. of Aetna’s compensation is now ten million dollars,” he pointed out. “These are for-profit companies. Insurance companies make money by withholding reimbursements to physicians or by not approving payment for a service we’ve provided.” To him, the question is why we deal with them at all. In his view, doctors need to understand that we are businessmen—nothing less, nothing more—and the sooner we accept this the better.

His position has a certain bracing clarity. Yet, if this is purely a service-for-money business, if doctoring is no different from doing oil changes, why choose to endure twelve years of medical training, instead of, say, two years of business school? I still believe that doctors remain fundamentally motivated by the hope of doing meaningful and respected work for society. Hence the responsibility most of us feel to take care of people even when their insurers exasperate us, or when they have no insurance at all. If we fail ordinary people, then the notion that we do something special is gone. I can understand wanting to escape the insurance morass. But isn’t there some other way around it?

In 1971, a thirty-three-year-old internist named Harris Berman decided to do things a little differently. He and a friend who had just completed his general-surgery training moved back to their home state of New Hampshire, to the town of Nashua. They joined up with a pediatrician, a family practitioner, and an obstetrician. Together they offered health care to patients for a fixed fee, without any bills to insurance companies. It was a radical experiment. They paid themselves fixed salaries of thirty thousand dollars a year, with no differences in income between specialties. They also bought reinsurance coverage to pay for costs that exceeded fifty thousand dollars, as Berman remembers it, in case a patient developed a catastrophic illness.

The scheme worked. Berman, who is now sixty-six years old, told me the tale. They called themselves the Matthew Thornton Health Plan, after a physician who was one of New Hampshire’s three signers of the Declaration of Independence. They were essentially an H.M.O., though a very tiny one. Within a short time, about five thousand patients had signed up. The doctors thrived, and there were remarkably few hassles. In the beginning, they didn’t have any subspecialists, so when patients were sent to an ophthalmologist or an orthopedist the Thornton doctors had to make an individual payment. Eventually, they asked the specialists to accept a flat fee each month and dispense with the paperwork.

“Some accepted,” Berman said. “And the effect on care was remarkable. The urologists, for example, suddenly became interested in having us understand which patients they really needed to see and which ones we could take care of without them. They came down and gave us talks—how to work up patients with blood in the urine and decide which ones you had to worry about. The ophthalmologists came down and told us how to take care of itchy eyes and runny eyes. They weren’t going to make more money seeing these unnecessary patients, and they found a way to make sure we became more efficient.”

After a few years, the Matthew Thornton Health Plan started to be cheaper than other insurers. Employers caught on and enrollment soared. Berman had to bring in more doctors. That’s when things got more complicated. “In the beginning, we were all committed,” he said. “We worked hard—long hours, a lot of dedication, young and hungry. Then, as we started to get bigger and bring in more staff, we found that others joined for other reasons. They liked the salaried life style—the idea that being a doc could be a job, rather than a day-and-night commitment. Some were part-timers. We began to see people looking at their watches as five o’clock approached. It became clear that we had a productivity problem.” When they tried to bring in specialists to work full time with the group, the specialists refused to accept the same salary as the others. In order to get an orthopedic surgeon to join, Berman had to pay him considerably more than what everyone else got. It was the first of many adjustments he had to make in how and what to pay his fellow-physicians.

Over the course of thirty years, Berman told me, he’d tried paying physicians almost every conceivable way. He’d paid low salaries and high salaries and still watched them go home at three in the afternoon. He’d paid fee-for-service and watched the paperwork accumulate and the doctors run up the bills to make more money. He’d come up with complicated bonus schemes for productivity and given doctors budgets to oversee. He’d given patients cash accounts to pay their doctors themselves. But no system was able to provide both simplicity and the right balance of thriftiness and reward for good patient care.

By the mid-nineteen-eighties, sixty thousand patients had joined the Matthew Thornton Health Plan, mainly because it had controlled its costs more successfully than other plans. It had become the second-largest insurer in New Hampshire. And now it was Berman and his rules and his contracts that all the physicians complained about. In 1986, Berman left Matthew Thornton, and it was later taken over by Blue Cross. He went on to become the chief executive officer of Tufts Healthplan, one of New England’s largest health insurers (where he also earned a C.E.O.’s income). The radical experiment was over.

In the United States in 2004, we spent somewhere around $1.8 trillion—15.4 per cent of all the money we have—on health care. Government and private insurance split about eighty per cent of those costs, and the rest largely came out of patients’ pockets. Americans seem to be reasonably happy with their care, but they haven’t liked the prices—insurance premiums increased by 9.3 per cent last year. Hospitals took about a third of the money; clinicians took another third; and the rest went for other things—nursing homes, prescription drugs, and the costs of administering our insurance system.

Physicians’ after-expense incomes are a fairly small percentage of medical costs. But we’re responsible for most of the spending. For the patients I see in the office in a single day, I prescribe somewhere around thirty thousand dollars’ worth of medical care—in the form of specialist consultations, surgical procedures, hospital stays, X-ray imaging, and medicines. And how well these services are reimbursed inevitably affects how lavish I can be in dispensing them. This is where income becomes politics.

I remember, nine years ago, getting the bill for the heart surgery that saved my son’s life. The total cost, it said, was almost a quarter-million dollars. My payment? Five dollars—the cost of the co-pay for the initial visit to the emergency room and the doctor who figured out that our pale and struggling boy was suffering from heart failure. I was an intern then, and in no position to pay for any significant part of his medical expenses. If my wife and I had had to, we would have bankrupted ourselves for him. But insurance meant that all anyone had to consider was his needs. It was a beautiful thing. Yet it’s also the source of what economists call “moral hazard”: with other people paying the bills, I did not care how much was spent or charged to save my child. To me, all the members of the team deserved a million dollars for what they did. Others were footing the bill—so it’s left to them to question the price. Hence the adversarial relationship doctors have with insurers. Whether insurance is provided by the government or by corporations, there is no reason to think that the battles—over the fees charged, the bills rejected, the pre-approval contortions—will ever end.

Given the politics, what’s striking is how substantial medical payments have continued to be. Physicians in the United States today remain better compensated than physicians anywhere else in the world. Our earnings are more than seven times those of the average American employee, and that gap has grown over time. (In most industrialized countries, the ratio is under three.) This has allowed American medicine to attract enormous talent to its ranks, and kept doctors willing to work harder than members of almost any other profession. At the same time, the politics of health care has shown little concern for the uninsured. One in seven Americans has no coverage, and one in three younger than sixty-five will lose coverage at some point in the next two years. These are people who aren’t poor or old enough to qualify for government programs but whose jobs aren’t good enough to provide benefits, either. Our byzantine insurance system leaves gaps at every turn.

A few days after the chairman of surgery offered me the job, I returned to his office and named my figure.

“That’ll do fine,” he said, and we shook hands. Now I am the one who’s too embarrassed to say what I earn. We talked for a while afterward: about how to fit research in, how many nights I’d have to be on call, how to keep time for my family. The prospect of my new responsibilities filled me with both exhilaration and dread.

As the meeting was ending, though, I realized that there was one final important question I had not brought up.

“What are the health benefits like?” I asked.

Tuesday, March 29, 2005

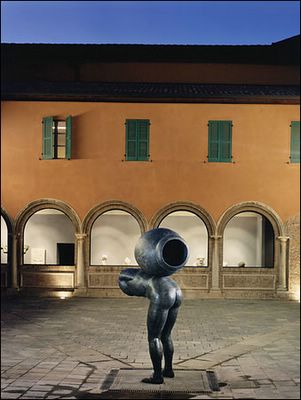

STYLE Our Town By MAURA EGAN

Reggio Emilia is a picturesque city about an hour east of Milan. Old men ride bicycles over the cobblestone streets, the women shop the open food markets in the piazza (the region could be called ''the cholesterol belt of Italy,'' since the country's top-shelf Parmigiano Reggiano, Parma ham and pasta are produced there) and the swarming schoolchildren look like something out of a Fellini film. It's all very quaint and Old World until you step into the cloisters of the nearby Church of San Domenico and discover a bronze figure -- headless, armless, genderless, a large urn sprouting from its back -- smack in the center of the courtyard. Industrial-type music, the sounds of a busy city, played every evening at dusk, accompanies the piece. This gleaming abstract sculpture, ''Less Than,'' by the Minimalist artist Robert Morris, is part of a continuing project by the Italian fashion house MaxMara and Reggio Emilia to introduce contemporary art into the daily life of the city. Last summer, Sol LeWitt painted the kaleidoscopic ''Whirls and Twirls 1'' on the ceiling of the reading room of the Panizzi Library, a 18th-century building in the center of town. ''We started with the easiest, the pretty colors,'' says MaxMara's chairman, Luigi Maramotti, who recognized that more challenging work might stump the natives. The Maramotti family has always had a big investment in the town, ever since Luigi's father, Achille, founded the company there in 1951 with the goal of bringing Paris high fashion, at affordable prices, to the ladies of Italy. The family is the major shareholder in the local bank, Credito Emiliano (which warehouses 300,000 wheels of the locally produced Parmesan, a vestige of a time when farmers left their cheese in the bank vaults as a guarantee for their loans); it owns the luxury hotel Albergo delle Notarie and a restaurant, not to mention acres of farmland on the outskirts of the city. Forty-five years later, Luigi Maramotti presides over the $1.5 billion business, which boasts 23 different clothing lines and more than 1,800 stores around the world. (Achille died in January at age 78.) And if Prada is known for its intellectual rigor and Dolce & Gabbana for va-va-voom sexiness, MaxMara has positioned itself as the ''quiet giant'' of the fashion industry. The company has maintained a value-over-frills philosophy, designing classic pieces like the perfect camel coat that outlast the whims of fashion. As Domenico Dolce, who scissored-out patterns there years ago (as did Karl Lagerfeld, but MaxMara doesn't believe in flaunting its designers like box-office stars) explains, ''On their level, nobody does it better.'' You witness that level of perfection in Maramotti, perched this day on an ergonomic chair behind an expansive glass desk in his office. In 2003, MaxMara moved into new headquarters, a modular affair designed by the London-based firm John McAslan & Partners. Maramotti's passion for details is wide-ranging -- from the ply of cashmere used for a camel coat (''The fabric is always the starting point,'' he says) to the choice of art that hangs in his office (a triptych by his friend Peter Halley, the American painter) to the location of the company cafeteria. He read reports that doctors advise humans to walk half an hour each day, so he made sure the canteen and the parking lot were situated a healthy distance from the actual offices. Company policy forbids eating at your desk, and employees are thus forced to get some fresh air during the workday. There are even buckets of umbrellas stationed at the exits for rainy days. Luigi, along with his brother, Ignazio, who is managing director, and sister, Maria Ludovica, who is in charge of product development, wanted to implement these utopian ideals outside of the workplace, which led to their current roles as modern-day Medicis. In addition to the artists' project, the family will open its museum-worthy art collection to the public in 2007. Achille amassed one of the most important collections in the country, with works by de Chirico, Morandi and Richter. ''Achille was one of these mythic figures,'' Peter Halley says. ''He was part of this generation of entrepreneurs after the war who believed that business and culture went hand in hand. Success meant participating in the arts.'' A large-scale piece by Richard Serra will be completed and installed in an industrial complex north of the town in 2006. The latest and possibly most ambitious component in the city's cultural overhaul is the design of the new train station, which will be on the high-speed line that links Milan to Rome. Maramotti, naturally, wanted a boldfaced architect for the project. He championed Santiago Calatrava, who put his native Valencia on the design map with his City of Science Museum and Planetarium and is heading up the $2 billion transit hub for the World Trade Center. ''I just called him up and asked him,'' he says matter-of-factly. But because it was suspected that townsfolk might resist a metal-and-glass structure jutting out of their serene countryside, Calatrava was invited to present his ideas at a town meeting. ''He was a hit,'' Maramotti says triumphantly. ''He drew pictures and then gave them all away to the children.'' Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

Monday, March 28, 2005

Liz Smith, the columnist, left, chatted with Donna Hanover last week at an event sponsored by Elle Magazine and Mount Holyoke College.

In the Blog Era, Liz Smith Wonders if There's Room for the Pro

By KATHARINE Q. SEELYE

Let's dish...

So LIZ SMITH was having dinner with NICOLE KIDMAN at New York's Four Seasons and it seems the actress really likes to pig out.

"Nicole ate the entire bread basket," Ms. Smith said. "Then she said, 'Let's have some of those fabulous fried shrimp.' " Ms. Kidman then plowed through a main course and finished with chocolate cake and ice cream, convincing the gossip columnist that the actress meant it when she said she did not believe in diets.

Okay, pretty tame stuff by today's gossip standards. But the gentle behind-the-scenes glimpse of celebrities is Ms. Smith's stock in trade. And it has helped her survive the increasingly cutthroat business of gossip-writing, an industry that has mushroomed over the last three decades and spawned scores of magazines, television shows, Internet sites and blogs that are consumed with all manner of people-watching and celebrity doings.

In an interview last week, Ms. Smith admitted that the gossip industry has become so pervasive and ruthless that it is difficult to break through with a distinctive voice.

"You can go to so many places now to get the down and dirty, I don't even try," she said. "It's really hard now to get a scoop. With the whole world writing gossip, where is the place for the professional gossip?"

Ms. Smith, who started her career as a columnist at The Daily News in New York in 1976, is now 82 and continues to pump out six columns a week. She has just signed another two-year contract with The New York Post and is in negotiations for another contract with Newsday. Her new book, "Dishing," comes out next month.

Ms. Smith said she was initially reluctant to take the job at The Daily News because, as she told her editors at the time, she thought gossip was dead.

Gossip-writing was a no-go for a time, after the industry collapsed in scandal in the late 1950's. But it got a second wind in the early 1970's with the introduction of People magazine, and now it is flourishing.

But Ms. Smith, who said she believed she was the highest-paid newspaper gossip columnist in the country - she was estimated to be making $1 million in 1998 - said she doubted she would be hired as a new gossip writer today.

Col Allan, editor in chief of The New York Post, agreed that Ms. Smith would have a hard time in today's world.

"It's rare for a successful columnist not to have a mean streak and she doesn't have a mean streak," he said. "These days it would be difficult to carve out a position for yourself without that, partly because people look for it."

Gone are the days when a single powerful columnist could make or break a career. At the height of Walter Winchell's influence in the late 1930's and 1940's, his column was syndicated in more than 2,000 newspapers; Ms. Smith is syndicated in 70 newspapers.

"Franklin Roosevelt used to give him tidbits," Ms. Smith said of Mr. Winchell. "Imagine that! Today, even serious reporters can't get the ear of the president."

Gone too are the days when columnists had individual identities. Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons, who created their own celebrity brands with their trademark chapeaux, have been replaced by interchangeable mass market magazines and faceless blogs.

But what sets Ms. Smith apart is that she doesn't trash her subjects. This helps her maintain access, but it also means her column often lacks the prerequisite of the day: edge.

Jeannette Walls, the purveyor of gossip at MSNBC, said of Ms. Smith: "She made a decision not to be nasty and not to exist on schadenfreude, and that's not a formula that would work today."

Ann Gerhart, who co-wrote The Reliable Source column for The Washington Post from 1995 to 1999, described Ms. Smith's modus operandi this way: "She's friendly with Lauren Bacall, so when Lauren Bacall updates her memoirs, Liz will throw her a bouquet and help boost sales. You have far better access when you're kind to people."

In today's gossip world, being kind is hardly an option. "The Internet and blogs have returned gossip to its earliest human roots - the kind of gossip that the priests told you was a venal sin," said Ms. Gerhart. "You can make it up. You can speculate wildly. You can accuse people of the most taboo practices, all in this sort of merry way."

In this free-for-all, some celebrities are branching into gossip themselves. Rosie O'Donnell, the former talk show host, is writing her own blog. Teri Hatcher, of "Desperate Housewives" on ABC, recently interviewed Ms. Smith for Interview magazine's May issue.

"The world has come full circle," Ms. Smith chuckled. "Anybody can be a gossip."

Publicity agents, too, are less reliant on the gossip columnists, partly because they have so many other outlets. "Press agents used to beg you" to write about their clients, Ms. Smith said. "But now they only want the cover of Vanity Fair or Vogue and they don't much care about being in the gossip columns. Most of the gossip columns have already treated their clients so badly, the agents don't want to serve them in any way. Gossip columnists generally have no conscience."

Leslee Dart, president of the Dart Group, a marketing and public relations agency specializing in the entertainment industry, agreed.

"Columnists now are willing to go further, divulging things that 20 years ago you wouldn't have seen and wouldn't have believed," she said in an interview last week after appearing with Ms. Smith at a forum sponsored by Elle Magazine and Mount Holyoke College.

Because of that, Ms. Dart said, some agents spend their time negotiating with columnists to protect their clients. "I know there are press agents who say to the columnists, 'If you don't write this, then I'll give you so and so,' " Ms. Dart said, adding that that was not her style. "My best advice to a client is that today's newspaper wraps tomorrow's fish. And a week from now or a month from now, we'll find a way of balancing it out.

"If someone's going through a public divorce and they feel the need to put something on the record, Liz will do that. She'll give you the opportunity to speak your mind, and because of that, people are more willing to sit down and tell her what's going on."

This kind of transaction makes Ms. Smith a further anachronism in her profession, where one of the newest entries, in Los Angeles, is a blog called Defamer, a title that almost begs its subjects to take it to court.

David Patrick Columbia, editor of NewYorkSocialDiary.com, a blog that reports on social events and the celebrities and socialites who attend them, said that where Mr. Winchell used his power to destroy people, Ms. Smith used hers to help people, including work on philanthropic projects and to promote literacy.

"She gives away her money," he said. "There are a lot of people whose rent she's paid. When I started my Web site, I hardly knew her, and she asked me if I needed to borrow some money. She asked me three times."

Even back in 1990 when Ms. Smith scooped the world with news of the breakup of Donald and Ivana Trump, she specialized in lending a sympathetic ear. Ms. Smith, then with The Daily News, allied herself with Ivana while Cindy Adams of The New York Post allied herself with Donald, a standoff that further inflamed New York's tabloid wars.

Ms. Smith is now Ms. Adams's colleague on The Post, where their work appears as part of Page Six, a gossip brand name that Mr. Allan, the editor, said was recognized the world over and that thrives even in the age of bloggers. "Page Six survives because people expect original content from it and they get it," he said. "It drives tremendous traffic to our Web site."

Gossip has been a circulation-builder for the tabloids, and advertisers like to appear on Page Six. But while more traditional newspapers have an uneasy relationship with gossip, they have devised their own versions of celebrity columns. Last week, both Richard Leiby, who has written The Reliable Source at The Washington Post since January 2004, and Joyce Wadler, who has written Boldface for The New York Times since 2001, said they were leaving their columns. Mr. Leiby said he was tired of writing ephemera, even though he was widely read.

"What people hunger for is insider, salacious material," Mr. Leiby said. "At The Post, that's a high-wire act. We're beholden here to the two-source rule or direct observation or document-based material."

Ben Bradlee, the former executive editor of The Washington Post, said the mainstream press was conflicted over how to handle gossip, even though it was one of the best-read parts of the paper. "We've had more bloody trouble with gossip columns," Mr. Bradlee said. "We deep down in our little constipated souls don't believe in gossip columns."

He said that articles in the 1960's and 1970's by Maxine Cheshire, The Post's long-time society writer, required his endless attention as an editor. "I spent more time with Max than I spent with Woodward and Bernstein," he said.

Ms. Walls, at MSNBC, said that editors had a love-hate relationship with gossip. "It brings in readers and viewers, but you lose credibility," she said. Ms. Walls, who wrote a book called "Dish" in 2000 about the evolution of gossip, said the Internet was "the perfect format" for gossip.

"It's quick and immediate, you can write short, and you can go into it and update it if something happens," she said.

The real-time pace of Internet gossip has made it difficult for newspaper gossip columnists to stay ahead of the curve. Mr. Leiby said that many people in the Post newsroom monitored Wonkette.com, a Washington blog, all day long. "She often has the lead on me because she's in real time," he said.

But Ms. Smith said that the blogs left her cold. She says she reads six newspapers a day, but not the blogs. "I only have a few years left to live, and I don't have time for them," she said. "Besides, I don't believe them."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Sunday, March 27, 2005

Dragon?

The Economist says various problems will hold China back.

By Bidisha Banerjee, Jesse Stanchak, and David Wallace-Wells

Updated Friday, March 25, 2005, at 2:51 PM PT

Economist, March 26

The cover package argues that competition from Japan and the United States, combined with internal corruption, poverty, and political scheming, will prevent China from controlling East Asia in the near future. At the same time, the region's stability is very much dependent on China's response to Taiwan and North Korea. ? Another piece criticizes the Tory response to gypsies in Britain. Because a 1994 law curtailed the number of places where they could park their caravans, gypsies have resorted to illegal camping. In response, the Tories have praised Ireland, where trespassing is a crime; they've also threatened to repeal the Human Rights Act, claiming that it helps gypsies challenge the government. Calling the Tories' proposals "slightly less useful than a sprig of lucky heather," the article points out that Ireland has substantially increased the number of legal camping sites. Also, when gypsies appeal to courts about this issue, their rare victories aren't because of the Human Rights Act.?B.B.

Harper's, April 2005

An article about the effects of strip mining in Appalachia focuses on Lost Mountain in Kentucky "before, during, and after its transformation into a western desert." The piece condemns the destruction of natural resources that we don't have immediate use for, and reflects on the sexual practices of liverwort. (A male liverwort "extends a tiny, umbrella-shaped antenna"; when rain strikes it, "sperm explodes inside that raindrop and bounces a couple of feet," in order to hit a female receptive to the "sperm-laden droplets.") It also laments the loss of the "oldest and most diverse" North American forests and bemoans the impact of modern mining practices (in which "entire mountaintops are blasted off") upon the people who live near the mountain. ? Another piece examines how Cubans have been forced to develop "what may be the world's largest working model of a semi-sustainable agriculture." In response to massive food shortages caused by the fall of the Soviet Union and the stringency of the U.S. embargo, Cubans have created predominantly organic urban gardens.?B.B.

Legal Affairs, March-April 2005

Two former applicants for clerkships with William Rehnquist?one who was hired, one who wasn't?debate the legacy of the chief justice. Despite conventional wisdom that Rehnquist has significantly advanced the cause of federalism during his tenure, the lawyer passed over writes

American Prospect, April 2005

The cover story argues that the pro-life movement has gained ground since Roe v. Wade by casting its arguments in emotional instead of legal terms and says its time for pro-choice advocates to adopt the same tactics to build sympathy for would-be mothers faced with a difficult choice. "The challenge for pro-choicers is to balance America's growing sympathy for fetuses with an equal?or greater?concern for women," writes Jodi Edna. "They must counter the image of a humanized fetus with that of a human, caring, and sometimes suffering woman?with a woman who has needs and feelings and morals." ... A movement to oust Sen. Joe Lieberman is under way in Connecticut, as detailed in a piece outlining both the gripes that many Democrats hold against the senator and hurdles confronting the "Dump Joe" movement in trying to unseat the incumbent.?J.S.

Scientific American, April 2005

Business practices might be a product of evolution, suggests a piece that explores how animal behaviors mirror economics. Through a variety of studies on chimpanzees, capuchin monkeys, and cleaner fish, Frans B.M. de Waal shows how concepts of supply and demand, reciprocity, and even valuing good customer service might have been handed down by our animal ancestors. "This evolutionary explanation of how for why we interact as we do," writes de Wall, "is gaining influence with the advent of a new school, known as behavioral economics, that focuses on actual human behavior, rather than abstract principles." ? A new painkiller has its origins on the ocean bottom, reports a piece on Prialt, a synthetic version of cone-snail venom that will be injected directly into patients' spines to treat certain types of chronic pain resistant to opiates and aspirin.?J.S.

New York, March 28

Ben Stiller is profiled as he prepares to open a new drama off Broadway. The 39-year-old actor is found wrestling with the age-old comedian's dilemma of how to be taken seriously as an actor and land the dramatic roles that have eluded him for years. "Apparently, once you've zippered your scrotum, dangled sperm off your ear, been Tasered, faked explosive diarrhea, and filmed yourself in an orgy involving a donkey and a Maori tribesman," writes Logan Hill, "some studios just won't trust you with serious material." ? Cablevision CEO James Dolan grants a rare interview in a piece delving into his public feud with New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his private battles with his father, Chairman Chuck Dolan, at family-run Cablevision, "the North Korea of the cable business."?J.S.

New York Times Magazine, March 27

The cover story looks at the exurban megachurch as a supplier of the social infrastructure otherwise lacking in the developing communities of the rural West. The complex maintained by the Radiant Church in Surprise, Ariz., functions as a Christian clubhouse for the boomtown: It offers a flat-screen TV lounge, video games for kids, an upscale coffee shop, bookstore, aerobics classes, and positive self-help sermons on such nontraditional subjects as sex and the stock market. "We want the church to look like a mall," says Pastor Lee McFarland, who believes casual churchgoers will eventually gravitate toward the church's evangelical core. "We want you to come in here and say, 'Dude, where's the cinema?' " ? A photo essay covers how field hospitals treat soldiers injured in the Iraq war. ? A profile of Benjamin Biolay relentlessly compares the singer to French icon Serge Gainsbourg and finds the younger chanteur a reluctant hero to a new generation of French pop.?D.W.

The New Yorker, March 28

In a piece that asks, "Do ads still work?" Ken Auletta focuses on advertising guru Linda Kaplan Thaler, who firmly believes that all publicity is good publicity. (Thaler thought up the enormously successful quacking duck commercials for Aflac, an insurance company.) Noting that the declining importance of network television has put an end to traditional advertising approaches, the article looks at the rise of product placement and Internet advertising. ? In a profile of Antonin Scalia, Margaret Talbot suggests that the conservative Supreme Court justice provides "the jurisprudential equivalent of smashing a guitar onstage." Claiming that Scalia appears to be "campaigning" for the position of chief justice, Talbot explores his disdain for the concept of a "living Constitution," and writes, "[I]t's hard to identify a Scalia Doctrine that speaks for the Court, as opposed to a Scalia Doctrine that speaks for Scalia."?B.B.

Weekly Standard, March 28

A piece excoriates former baseball player Jose Canseco, whose allegations that his former teammates used steroids led to last week's congressional hearings into steroid use: "Jose Canseco is against smoking and stress. He's for the environment. He's a liar. He's a criminal. He's a tattletale. He changes his story from audience to audience. Why isn't this guy in Congress?" ? Another piece defends

Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News & World Report, March 28

Condoleezza Rice: In an extremely upbeat appraisal

Women international: Newsweek profiles Mukhtar Mai

Odds and ends: Time's cover grapples with the prevalence of indecency on television. One year after Janet Jackson's infamous "Nipplegate," there's a new FCC head, and Congress is attempting to increase the agency's power to regulate decency?maybe even on cable. Arguing that indecency is a matter of context, the piece insists that people "don't want absolute rules. They want boundaries: they just want to know where the cultural deep end and the kiddie pool are." ? U.S. News' cover examines FBI Director Robert Mueller's struggle to transform

Bidisha Banerjee is a Slate editorial assistant.

Jesse Stanchak is a Slate intern.

David Wallace-Wells is a Slate intern.

Article URL:

Demi Moore

The mother of all actresses.

By Bryan Curtis

Posted Wednesday, March 23, 2005, at 3:50 PM PT

When was the last time Demi Moore was in a picture? Not a motion picture?mercifully, those seem to have stopped?but a magazine cover? Demiologists date the artist's last major work to the August 1991 issue of Vanity Fair, in which she posed nude and pregnant, though a vocal minority argues for the August 1992 issue, in which she posed nude and lathered with body paint. To those two masterworks, let us add a third: this week's cover of the Star, which announces, "DEMI PREGNANT AT 42!" The magazine reports that Moore and her boyfriend, Ashton Kutcher, 27, are expecting a baby in October. This is big news. When not carrying a child, Moore comes off as an unsmiling, wooden actress that America tends to root against. Pregnant Demi, on the other hand, ignites our greatest sympathies and passions. This is the actress who spans genres, even decades?the Demi we deserve.

Of course, she might not be pregnant. But while Moore's handlers issue hazy denials?"She cannot at this time say she is pregnant"?the Star's breathless article dishes out the specifics. Moore learned the news on March 4, the magazine reports, then phoned Ashton and yelped, "Honey, I'm pregnant!" Already, the tabloid has begun to portray Demi in a more sensitive and respectable light. It reports that she has forsaken her regular diet of Red Bull and cigarettes. Moore's three daughters?Rumer, Scout, and Tallulah Belle?are said to be overjoyed at the news. Why, there's even talk of a wedding, to ensure the Kutcher baby enters the world as part of an honest union.

Has an actress ever leveraged pregnancy more effectively than Demi Moore? The recent births by Gwyneth Paltrow and Julia Roberts reminded us of everything we love about them. Moore, by comparison, uses pregnancy to make us forget what we detest about her. Moore's most celebrated pregnancy was her second, at 28, when she posed for Annie Leibovitz's infamous Vanity Fair cover shot. The movie Moore was ostensibly promoting (The Butcher's Wife) was wretched and seen by no one. But the photos were so incendiary that Moore was elevated to the role of feminist saint. The withering attacks from talk-show hosts and American Enterprise Institute fellows only made her more so. "People can't bear the idea that I could be sexual and provocative, and still be a nice person with a nice family and a nice husband," she said later.

Pregnancy has the further effect of burnishing Demi's biography: It makes her hardscrabble childhood seem more poignant. She was born Demetria Guynes in Roswell, N.M., in 1962. Her mother, Virginia, named her after a beauty product. Her father disappeared before she was born; her stepfather, Danny Guynes, divorced her mom and killed himself when Demi was still in high school. Demi says her family moved 48 times during her youth. Years later, her mother descended into alcoholism, rebuffed Moore's attempts at intervention, and wound up replicating her daughter's nude poses for a low-end magazine.

Motherhood does more than animate Demi's public persona. She says it invests her movies with previously unnoticed depth. This will come as a surprise to some viewers, who thought Moore's movies were primarily vehicles for her to cry and remove her clothes. Moore has said, "When I start to reflect on films I've done, starting with Disclosure to The Scarlet Letter, then The Juror, Now and Then, and Striptease, even though they're very different, they have elements that have a general theme ? a very maternal theme." Moore says she idolized Hester Prynne for years before acting in The Scarlet Letter; never mind the scene in which Moore lovingly inspects her body in the bathtub. Striptease was the inspiring story of a single mother that only incidentally contained nude dancing. Some matriarchs are harder to figure?was Disclosure's Meredith Johnson the mother of high tech??but one admires her efforts, nonetheless.

Pregnancy also gives Moore what Hollywood starlets really want: creative control. "Gimme Moore," as one studio executive dubbed her, spent her career terrorizing directors into caving to her demands. But never did she wield more influence than at the birth of her oldest daughter, Rumer, in 1988. Moore traveled with then-husband Bruce Willis to Paducah, Ky., where he was shooting In Country. She commandeered a local hospital, placing three video cameras and a director named Randy in the delivery room. When her labor started, the cameras rolled, with Willis looking brave if a bit bewildered, as in Die Hard, and Moore panting and moaning, as in Indecent Proposal. When the baby's head finally emerged, Moore was said to turn to the director and grunt, "Did you get that?" Though largely unseen, it remains a canonical performance, just behind her work in G.I. Jane and Blame It on Rio.

Moore appeared last weekend on Saturday Night Live alongside Kutcher, in a gray wig and a floral-print dress. The obvious gag was that Moore was 15 years older than her paramour, but if she is indeed pregnant, the skit carried a deeper meaning: Moore was angling to become Hollywood's oldest expectant mother. And Moore may not stop with one more. Pregnant or not, her spokesman says the actress wants more "children"?plural?which could guarantee regular Demi births deep into the new century. "Pregnancy agrees with me," Demi once said. So much more than acting.

Bryan Curtis is a Slate staff writer. You can e-mail him at curtisb@slate.com

Article

Michael Jackson gestures to fans as he arrives Thursday at the Santa Barbara County, Calif., courthouse

The man in America's mirror

Believe it or not, the Michael Jackson trial is more than a freak show. Yes, it's a celebrity-sex wallow -- but it's also a crucible for our unresolved questions about crime, fame, race and punishment.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

By Farhad Manjoo

March 26, 2005 | To most people, taking the Michael Jackson case seriously is a contradiction in terms. As much as Jackson is known for having once been a great performer, he is now known for being a freak. With his chimp, hyperbaric chamber, mysterious illnesses, dangling baby and, most of all, ever changing face, Jackson has become a regular player in the Bat Boy

But I'm here to tell you that Jackson's trial on charges of child molestation is more important than you think it is. The case presents us with a rich seam of American obsessions, a combustible cocktail of celebrity, sex, race, mass media and the administration of law and order in our society. It gives us an opportunity to understand the method to Jackson's apparent madness, to examine the ways in which he has, throughout his career, mined freakishness for its utility to him as a star. Here's a musician who hasn't recorded a great album in more than a decade and nevertheless remains, for better or worse, a cultural obsession, a national figure to be mocked or cried over, lamented or prized.

To begin with, Jackson can't be dismissed simply as a freak. Seth Clark Silberman, a professor of gay and lesbian studies at Yale University, who is a fan and a scholar of Jackson, reminds us that the performer has long engineered his own career and image. As long as Jackson's been popular, he's been weird. A better way to put it is that he's popular because he's weird, because he knows that oddness is intriguing, and that it's better that the public thinks of him as being a strange man than not think of him at all.

In a lecture that Silberman gave at a conference focused on Jackson at Yale last fall, the professor pointed to an assessment that Steven Spielberg once made of Jackson: "He's in full control," the director said. "Sometimes he appears to other people to be sort of wavering on the fringes of twilight, but there is great conscious forethought behind everything he does. He's very smart about his career and the choices he makes."

Silberman argues that even in the infamous 2003 documentary, "Living With Michael Jackson," by the British journalist Martin Bashir, Jackson played up his oddities in a (rather brilliant) attempt to keep us interested. The whole world thinks of Jackson as odd; if he'd disappointed Bashir by acting normal, nobody would have watched. So, instead, he decided to act stranger than any of us might have ever imagined. Afterward, we couldn't get him out of our heads.

In the documentary, though, Jackson's circus act backfired on him. Silberman says that while watching the scene in which Jackson is holding hands with a 12-year-old boy and proudly declares that there isn't anything wrong with sharing his bed with children, "I had to pause the TiVo and say to the TV, 'Michael, what are you doing? Why would you do this now?'" It was this scene, prosecutors say, that set in motion the current child molestation case.

The trial has been carrying on for about four weeks; we're now at the halfway point, with the prosecution just about done presenting its case for Jackson's guilt. At the center of this case are two boys, Gavin, the former cancer patient shown in the documentary, and Star, Gavin's younger brother. Gavin claims to have been molested by Jackson, and Star says he witnessed acts of molestation.

These acts are alleged to have occurred after the Bashir video was made, but both boys also testified that Jackson acted inappropriately with them before that. For instance, Jackson gave Gavin a computer on the first night that he met the boys at his Neverland Ranch in the summer of 2000, and, presumably in an effort show them that the computer was in working order, he introduced them to pornographic Web sites. "Got milk?" Jackson is said to have remarked when showing the boys a well-endowed woman who struck his fancy -- proof if ever you needed it that those commercials are evil.

Gavin, Star and their older sister, Davellin, who have all testified, say that they spent some time at Jackson's ranch in late 2000 and 2001 -- but that Jackson suddenly cut off all communication with them and they didn't talk to him for more than a year. Then, one day in 2002, Jackson called Gavin more or less out of the blue and invited him to Neverland Ranch to participate in a film -- the Bashir film.

This series of events is important; it suggests that Jackson had forgotten about these children for some time and decided to call them only when he thought they could be useful to him in a documentary. As Silberman suggests, there was some calculation to Jackson's behavior in the film. He may have been using the kids specifically to show the world that he was not going to shy away from past indiscretions and in fact that he was going to embrace, in an aggressive manner, the world's suspicions about him.

Instead of making the public think that Jackson was merely kooky, the Bashir video was deemed beyond the pale. In 1993, Jackson barely avoided a trial when another child accused him of molestation; he paid that accuser $20 million to keep the charges out of court. With the Bashir video, the public had finally had enough with Jackson's winking at molestation. The film ruined Jackson, the prosecution says, prompting him to attack the children who were featured in the video.

It was only in the weeks after the Bashir video aired, the prosecution argues, that Jackson molested Gavin. Gavin testified that he and Jackson were together in Jackson's bed when Jackson brought up the subject of masturbation. He said that Jackson told him that masturbation is natural, and that men who didn't masturbate would become "kind of unstable" -- they would try to rape women or have sex with dogs. "And so I was under his covers, and then that's when he put his hand in my pants and then he started masturbating me," Gavin testified. He said that a similar incident occurred a few days later, and that he thinks, but can't be sure, that there were more incidents as well. "In my memory, it was only twice, but I feel it was more than twice," Gavin said. "But I only remember it twice."

Star testified that on two occasions, he went up to Michael's open bedroom door and saw the pop star masturbating while fondling his brother, who was asleep or passed out on the bed beside Michael. Jackson "had his hand in his pants, and he was stroking up and down," Star said. His brother was snoring. Jackson "had his eyes closed."

Life with Jackson appears to have been an awful cross between Romper Room and the Playboy Mansion, where every gag was at once juvenile and perverse. Jackson hosted odd swearing contests in which he encouraged the kids to string together all kinds of bad words. He made crank calls to strangers, asking women how big their "p-u-s-s-y" was, Star said in court. Once, while Star and Gavin were watching a movie, Jackson walked into the room completely naked with a "hard-on," Star testified, and the brothers were "grossed out." Star also described an incident in which Jackson pretended to have sex with a mannequin he keeps in his room. "He was -- one time -- he was jerking around and he grabbed the mannequin, and he was pretending like he was having intercourse with it," Star said. "He was fully clothed. He was acting like he was humping."

The lurid details make the case easy to dismiss as tabloid fodder. But Thomas Lyon, an expert on child-abuse law at the University of Southern California Law School, believes otherwise. He argues that the high-profile trial is important precisely because it resembles many other molestation cases. "It could have a profound effect on how people see cases involving children," he says. Depending on the outcome, it may dictate "what kinds of legal actions we take against them."

Currently, there are about 90,000

Lyon points out that Jackson's fame doesn't eliminate the similarities between his case and other child molestation trials. For all its apparent freakishness, he says, the Jackson trial is proceeding in just the way most child-abuse trials do. "This case can teach the public about the M.O. of the typical molester," Lyon says.

Most people believe that a typical child molester is a "violent offender who picks up kids he doesn't know" and abuses them. But that's not at all how most cases occur, Lyon says. "If these charges are true, Jackson is the classic molester in terms of how he approached his victims.

"First step is, Jackson introduces him to alcohol. Then he introduces him to pornography. Then he talks to him about how it's natural to masturbate. Then, fourth step is, he does something to the child. And then he tries to get the child to do something to him. This is classic. The molester befriends the child, he corrupts the child, and then he moves toward the sex act."

Not only did the alleged molestation in Jackson's case parallel most molestation cases, so too has the courtroom proceeding run according to a similar pattern, especially when it comes to the children's testimony.

On the stand, Gavin, Star, and their older sister Davellin have sketched a rather clear broad picture of what happened during their interactions with Jackson. But they have also been inconsistent, and sometimes unbelievable, in their details. Reading through the transcripts of the case, especially during the times that each of them was cross-examined by Tom Mesereau, Jackson's pitch-perfect defense attorney, is a frustrating exercise. You're constantly trying to believe the kids -- what they say is too terrible to dismiss -- but at the same time you're wondering if they've fooled the D.A. and half the country into believing awful things about Jackson.

Why can't they remember dates? Why can't they explain why they said one thing before and are saying another thing now? What should you make of their admissions that they've lied to juries during a previous case? Are they trying to scam Jackson?

Lyon explains that inconsistencies are standard in child abuse cases. "The media is acting surprised at how terrible the children are doing on the stand but the kids are performing exactly as predicted," he says. "They're showing inconsistencies that any witness would show, and because they're children, they're explaining their inconsistencies more poorly, which is normal." Watching this case might give the public "a better appreciation for how hard it is for prosecutors to go after these guys," Lyon says. "It raises public awareness for how difficult it is to prove child molestation."

He notes that if the defense is successful in convincing the public and the jury that the kids are lying, there's a danger that people may become more skeptical of child accusers in general. That's especially because most incidents of child abuse are more difficult to prove than the ones alleged in this case, Lyon says. "It's true that in most cases you don't have the money motive," he says, referring to Jackson's defense team's theory that the family accusing the entertainer only wants money from him. "Yet in most normal child abuse cases you don't have this much evidence. You don't have an eyewitness. You don't have possible previous victims. You don't have the alleged molester acknowledging on tape that he sleeps with boys in his bed." If people don't believe the accusers in this case, they may not believe the accusers in most other cases, either.

Because Jackson is a wealthy superstar, there are certainly some major differences between this case and most child molestation cases. The prosecution alleges that Jackson used his stardom and wealth to lure Gavin into his trap; the defense, meanwhile, says that Jackson is being set up by Gavin's family specifically because he is wealthy. As such, says Robert Weisberg, a criminal law professor at Stanford, the Jackson case may be seen as "not just a trial of one of the most famous people on earth," but it "may truly be a trial about the phenomenon of celebrity."

In a sense, each side is asking the jury to weigh the power of Jackson's stardom, and to decide which side -- Jackson's side, or the boy's family's side -- was more willing to trade on that celebrity for gain. Because molestation cases are difficult to prove, Jackson may not be convicted of actually touching Gavin inappropriately, Weisberg says. But Jackson may be found guilty with lesser crimes having to do with his inappropriate behavior, such as giving the boys alcohol or porn. In such a scenario, Jackson's crime would fall into a kind of gray area, and he would really be convicted for "perverting or exploiting his celebrity," Weisberg says. "It wouldn't be that he raped children. The crimes would be somewhat more inchoate and amorphous. It would have to do with the fact that he wields extraordinary power over people, and he would be found guilty of abusing that power."

While there may be a great deal at stake in this case, it's not clear the version we are watching on TV is conveying what's important. Indeed, when you look at how the Jackson case plays on TV, it's not unusual to think back on the time of O.J. Simpson with no small bit of nostalgia.

It's true that you may have considered it inconsequential at the time, but that case, on reflection, can be called significant. The O.J. Simpson trial laid bare the deep racial divisions in our society. Through it, we learned of the pervasiveness of police misconduct, about jury nullification, the limitations of DNA evidence, deficiencies in domestic violence law, and the perils of televising court cases. The case inspired some positive changes in the law, but it also shook our faith in the courts.

"It was a disaster for the American perception of criminal justice," says Weisberg. "It fed into all the Archie Bunker myths of how the criminal justice system works -- that money enables you to win false acquittals, that everybody lies, and that people get away literally with murder."

Still, coverage of the Simpson case largely stuck to the facts in the courtroom. Today, the coverage of cases like Jackson's offer opinion over fact, constant shouting, as the New Republic's Jason Zengerle recently pointed out in a fine dissection

These days, "viewers can watch legal pundits yell at one another as they debate guilt and innocence, life and death, on any number of programs," Zengerle writes. Mark Geragos, who defended Scott Peterson and initially represented Jackson as well, tells Zengerle that "Court TV has taken what's happened in the political arena with Fox News and extended that to the legal arena ... It's the Fox-ification of the legal arena. And it's a significant problem."

With the Jackson case, coverage has slipped even more, making it now nearly impossible to determine anything important about the case from a nightly cable show.

During the Simpson case, "you could have analysts like myself sit up and talk and discourse on race, on domestic abuse, the issues of interracial marriage," says Earl Ofari Hutchinson, a cultural commentator who wrote a book on the trial and often appeared on CNN during that case. "It was almost an educational forum."

Hutchinson still frequently goes on TV to discuss legal cases -- I spoke to him just after he'd done Bill O'Reilly -- but he says that the whole experience is dumbed down these days, especially when it comes to Jackson. "Do you hear any of the very similar issues routinely raised in the media? Are there child-abuse experts, criminal justice experts on these talk shows? They can easily do the same thing they did with O.J. But the decision was made to treat this as a celebrity peep show. It's titillation driven, not information driven."

In addition to talking about child molestation, Hutchinson says that he would like to discuss the differences in the racial dynamics between this case and O.J. Simpson's. However, given Jackson's odd racial status, observers on race and law have to admit they're perplexed.

Christopher Bracey, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis, who is an expert on how racial questions affect the law, remembers that Simpson had an ambiguous racial status at the time of his trial; he'd married outside his race and was considered at the very least not quite concerned about African-Americans. But blacks embraced him during his case. Now, "with Jackson, it's like O.J. multiplied by 10," Bracey says. "He's in racial and cultural exile."

Still, Bracey says he found it interesting that "when the initial allegations were raised, the Nation of Islam came to his side.

Early in March, before many of the most important witnesses had taken the stand, the Gallup Organization ran a survey

But both Bracey and Hutchinson suggest that such disparities won't persist after the verdict is handed down. If Jackson is found guilty, blacks aren't going to rally around him, as they did around O.J. Simpson. That's simply because many African-Americans sensed that what they believed happened to Simpson -- that he was framed by corrupt cops -- could realistically happen to any one of them. What's happening to Jackson doesn't carry the same sense of victimization.

"There's been a decade of suspicions about him," Hutchinson says. "We know about the settlement. We know he's had these young boys in his bed -- the suspicions are so deep, the feeling is this guy is tainted. And so blacks will say, 'Why would we want to rally around a child molester?'"

Significantly, the judge in the case has run a tight ship, treating Jackson as fairly as any other defendant. Here's Michael Jackson, one of the most famous, most wealthy people in the world, getting a fair trial and being treated like everyone else, a lesson at odds with what happened to Simpson. "Ever since O.J. Simpson, when rich people go on trial, I think the public wonders if the same standard will be applied to them," says Jim Hammer, a former San Francisco prosecutor and frequent legal analyst for Fox News. "I think so far, here, the same standard has been applied -- and that sends an important message. In that courtroom you're like any other American."

And really, Hammer says, "I think the fact that there is a trial at all is a victory for the system. In 1993, he subverted justice. It's outrageous that you can buy off a victim with $20 million. Working folks can't do that. It's crazy that in a serious crime like child molestation, all that kept you out of jail was $20 million. So who knows -- maybe these are false allegations, maybe they're true. I don't know. But there is some victory in forcing the rich guy to stand trial like everyone else."

Any day now, Jackson's lawyers will rise to his defense.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

About the writer

Farhad Manjoo

Sound Off

Send us a Letter to the Editor

Related stories

When Michael Jackson was cool

Michael was the ultimate heartthrob to my '70s high school girlfriends. But my teenage daughter sees him as only a scary freak who can't stand living with skin the color of hers.

By Susan Straight

06/07/04

Rocking Jackson's world

The prosecution opens its case by focusing on a documentary about the pop star's life at Neverland.

By Dan Glaister

03/01/05

Salon.com

Saturday, March 26, 2005

Truly, Madly, Guiltily

By AYELET WALDMAN

HAVE been in many mothers' groups - Mommy and Me, Gymboree, Second-Time Moms - and each time, within three minutes, the conversation invariably comes around to the topic of how often mommy feels compelled to put out. Everyone wants to be reassured that no one else is having sex either. These are women who, for the most part, are comfortable with their bodies, consider themselves sexual beings. These are women who love their husbands or partners. Still, almost none of them are having any sex.

There are agreed upon reasons for this bed death. They are exhausted. It still hurts. They are so physically available to their babies - nursing, carrying, stroking - how could they bear to be physically available to anyone else?

But the real reason for this lack of sex, or at least the most profound, is that the wife's passion has been refocused. Instead of concentrating her ardor on her husband, she concentrates it on her babies. Where once her husband was the center of her passionate universe, there is now a new sun in whose orbit she revolves. Libido, as she once knew it, is gone, and in its place is all-consuming maternal desire. There is absolute unanimity on this topic, and instant reassurance.

Except, that is, from me.

I am the only woman in Mommy and Me who seems to be, well, getting any. This could fill me with smug well-being. I could sit in the room and gloat over my wonderful marriage. I could think about how our sex life - always vital, even torrid - is more exciting and imaginative now than it was when we first met. I could check my watch to see if I have time to stop at Good Vibrations to see if they have any exciting new toys. I could even gaze pityingly at the other mothers in the group, wishing that they too could experience a love as deep as my own.

But I don't. I am far too busy worrying about what's wrong with me. Why, of all the women in the room, am I the only one who has not made the erotic transition a good mother is supposed to make? Why am I the only one incapable of placing her children at the center of her passionate universe?

WHEN my first daughter was born, my husband held her in his hands and said, "My God, she's so beautiful."